Some 2,000 people showed up to the Wiltern Theater in December and paid up to $120 to see Drunken Tiger, Yoon Mi Rae and Bizzy perform live.

It was enough to fill the theater, but it was nothing compared with the 18,000 people who packed the Staples Center to see Girls’ Generation and Super Junior sing and dance to heavy bass and synthesizers.

So who are these artists you almost certainly have never heard who bring screaming masses to their feet?

They are part of the latest musical craze: imported Korean pop music, or K-Pop.

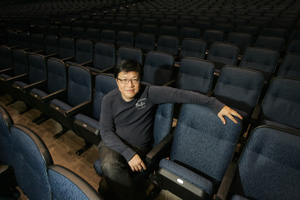

Its epicenter is Los Angeles and the man behind the movement is C.S. Hah, founder of Miracle Mile concert promoter Powerhouse, who has made the unlikely transition from newspaper reporter to the premier promoter of K-Pop.

Los Angeles is home to some 300,000 Koreans, the largest immigrant community outside of that country, but even Hah has been taken aback by how quickly K-Pop has caught on – and not just with ethnic fans. He recalls selling 7,000 tickets in six hours for his company’s first Staples Center show in 2010.

“I trusted that it was going to sell well. I didn’t expect the sales to be that hot,” he said.

Tickets sold for $40 to $180 to the SM Town show, named after the South Korean music label that provided the artists, SM Entertainment. Hah noted that 70 percent of the ticket buyers did not have Korean names.

Some compare K-Pop’s commercial prospects to the Latin pop explosion of the 1990s when such artists as Ricky Martin had hit singles. Others draw comparisons to the boy band bonanza of that decade featuring the Backstreet Boys and ’N Sync.

Now, the action has caught the attention of the world’s largest concert promoter and ticketing company – and Hah’s rival. Beverly Hills’ Live Nation Entertainment has recently started staging K-Pop shows as well.

The company already took away last year’s SM Town festival – considered the world’s premier K-Pop show – from Hah and staged it in Madison Square Garden in New York in October. The full-day festival featured artists signed to SM Entertainment. The show also has visited the world’s largest cities, including Tokyo and Paris.

What’s more, Live Nation opened a Seoul, South Korea, office last month to help export K-Pop, company Chief Executive Michael Rapino said in an e-mail to the Business Journal.

Citing a quiet period before the company’s upcoming earnings report, Rapino would not comment further.

K-Pop, which originated in Seoul, is only about 15 years old, not coincidentally about the time that browsers such as Netscape opened up the Internet to the general public; the genre has benefited greatly from online buzz.

The genre’s signature act is the so-called single-sex idol group, much like the Spice Girls or ’N Sync – except that they are larger with perhaps a dozen members. The acts, which dance and sing in a mixture of Korean and English, are often formed through open auditions, and then trained and managed by companies such as SM.

K-Pop also covers other genres of popular Korean music, such as R&B, rock and rap.

The groups gained popularity in Japan and other Asia Pacific countries by the early 2000s, and the music still tops charts there by offering energetic shows from artists often dressed in skimpy outfits, by Asian standards.

K-Pop came to Los Angeles in 2002 when Hah became L.A.’s ambassador to the genre by chance.

While working as a news reporter at the Korea Times, the paper’s management decided to start staging special events to create a revenue stream and engage readers. Every reporter was asked to submit ideas. Hah, who had seen the Internet buzz on K-Pop, suggested the paper look at staging a music festival. The paper gave Hah’s idea a shot, naming the event the Korean Music Festival and picking the Hollywood Bowl as its venue.

When the 18,000-seat venue was sold out in two weeks, Hah was encouraged. But when it sold out again the next year, he took a closer look at the ticket buyers on the database. He knew he was on to something bigger than an ethnic music festival: There was an astonishing number of fans with non-Korean last names.

Since then, local K-Pop events have only expanded further into the mainstream with more ethnically diverse crowds. Among the popular performers has been Rain, a male solo act who broke ground for future acts.

“The non-Korean audience has grown since then,” Hah said. “Thousands of them are gathering now to see the shows.”

After staging his sixth Korean Music Festival in 2008, he decided to leave the newspaper to devote his energies full time to promotion. Powerhouse produced his first show, for R&B duo Fly to the Sky at the Walt Disney Concert Hall in July of that year and his business reached new heights when he partnered with AEG to host the SM Town festival at Staples Center in 2010. He promotes six to seven K-Pop shows a year now, with some tours spanning multiple cities.

Hah wouldn’t disclose what percentage he takes from ticket sales, but said he makes deals that vary with each artist depending on their popularity. To promote a relatively unknown artist, he takes a larger back-end share of profits. There is no doubt that there’s money to be made.

The average ticket price for the SM Town show at Staples Center was $116 and given the capacity crowd of 18,000, the box-office gross would have totaled nearly $2.1 million. Still, producing an arena show costs well into the six figures, even before paying dozens of artists and managers.

Full blast

However, Hah’s promotional costs may be less given how young and tech-savvy K-Pop fans constantly message, use Twitter and visit their Facebook page. One music video for SM Entertainment’s Girls’ Generation has 64 million views on YouTube.

In fact, Hah said he buys few advertisements and instead relies on a list of 12,000 e-mail registrants to whom he sends information about upcoming shows. Those are the people who disseminate the information for him. And that’s largely how he filled the Nokia Theater recently when Korean soul singer Kim Bum Soo performed.

“The density and the loyalty of that fan base is much higher than the general public online,” he said.

Now, Hah is up against Live Nation, which first got into the genre when it promoted the 2010 tour of girl group Wonder Girls. The group was fresh off an arena tour opening for teenage sensations the Jonas Brothers and went on to play solo gigs at midsize venues such as the Fillmore in San Francisco.

To some, Live Nation’s involvement indicated a turning point in the evolution of K-Pop from a below-the-radar niche to a commercially viable product.

“The fact that you have large companies involved shows that it has become part of the broader concert business,” said Gary Bongiovanni, editor of concert industry trade publication Pollstar.

Still, the role of the niche promoter isn’t over. Large promoters such as Live Nation and AEG will often choose to co-promote shows with smaller companies.

Just last week, Powerhouse announced that it will co-promote with AEG Live the first U.S. concert for Korean group FT Island in March.

The long-term prospects for the genre aren’t fully known, even by the man who brought the phenomenon to Los Angeles.

“We’ll see how it goes,” said Hah. “In the meantime, I’ll continue to do what I’ve done.”