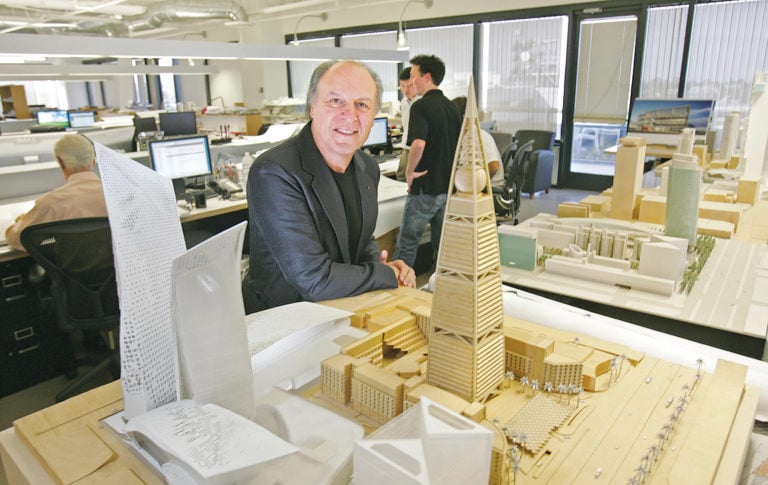

Herb Nadel is one of the most prominent architects in Los Angeles County. During his five-decade career, he has designed well-known projects ranging from the Westwood Center office building to the LAX Gateway public art project – that’s those light towers – to downtown L.A.’s Union Rescue Mission. But Nadel, 70, had anything but a traditional path to success. He was a miserable student whose parents took little interest in academics. It was only a fateful turn in the Coast Guard after failing out of Santa Monica City College that launched him toward success. In the maritime service, he weathered extreme anti-Semitism that put his life in danger, making him grow up rapidly. Almost four decades later, the firm he founded in 1973 boasts some 90 employees and has a strong international presence. Nadel sat down with the Business Journal in his stylish West L.A. office and spoke candidly about his life, becoming emotional when discussing difficult topics – such as the deaths of two siblings and his 30-year-old daughter. He also talked eagerly about the way he spends his free time – skiing, golfing and traveling the world with his companion, Jeannine Sefton – and how he plans to wind down his career.

Question: When did you know you wanted to be an architect?

Answer: When I was 9. I used to draw all the time. When I was a little kid I had asthma and I didn’t get to go out and play. When I did go out I would go to construction sites in the neighborhood and I would steal scrap lumber and build little houses in my backyard. My father at that point in his life was a house painter and he was doing a house in Benedict Canyon for an architect, Richard Frazier. He had a house with post and beam ceilings, Danish modern furniture and area rugs. We lived in Venice in a little tiny bungalow, and I went to the house and it was beautiful. He had a studio and I went down there and I saw all these drawings. And to me it was like the lights went on. I couldn’t believe what I saw. And he told me what an architect was. Up until that point I thought these little houses and apartment buildings in my neighborhood got built by the carpenters. I was very inspired by him.

So did you pursue it in school?

I never wavered from what I wanted to do but I have to confess, I barely graduated Venice High School.

Why?

I liked to draw, I liked architectural classes, but by the time I was ready to graduate high school I was getting D’s and F’s, and I couldn’t begin to tell you why. I’d been working since I was 11 years old. I had been making money to buy my own clothes. My father wasn’t a very hard-working individual. All of our family is middle-class, upper-middle-class people – my aunts and uncles on both sides. Everyone did something. Somehow my father didn’t. School was something I just couldn’t get interested in. I was taken to the principal’s office my senior year and they were going to throw me out. And they said, “You know you could accomplish things, you have a brain.” They might as well have been talking to a 1-year-old. I begged my way out of high school and I went to Santa Monica City College (in 1958) and I got all F’s. They threw me out.

If you weren’t studying, what were you doing?

I used to play chess all the time. If you would say what were you doing with your time? Why didn’t you buckle down? I don’t know why. Today maybe they would say I had ADD. When I wanted to learn something it was easy. When I got thrown out of Santa Monica City College it was a big wake-up call. A friend of mine said, “You know you are going to get drafted.” He was in the Army and they beat him up. They slapped him around and kicked him in boot camp. So I decided, rather than join the Army, I would join the Coast Guard.

I understand you had a life-changing experience with the Coast Guard.

When I joined the Coast Guard I got there on a Friday and they shave your head and give you uniforms. I was in Alameda, Calif. On Sunday, we all went to church. Now, I’m not an observant Jew but I consider myself very Jewish. I was never in a church in my whole life. There was a cross. There was a chaplain. It was sort of nonsectarian but it was a very Christian service. It kind of made me uncomfortable because in high school I had gotten in some fights. Someone told me that they had Jewish services on Thursday night, not on Friday night, which is traditional. You could make requests of your company commander. (Then) this incident happens to me and I knew my life changed. They had us all lined up and I made my request to my company commander, whose name was Mr. Roberts. I said, “I understand that there are Jewish services on Treasure Island on Thursday night.”

What did he say?

The guy went out of his mind. He was 5-foot-9, maybe 190 pounds and one solid muscle. He was a scary guy. I could feel the terror in this guy. He looked at me and started snorting. He said, “I am going to give you a chit to go to this,” and he called me all kinds of names. I took the thing out of his hands and I handed it back to him and said, “Mr. Roberts if you don’t want me to go I won’t go.” And he called me all kinds of names. The one thing I am grateful to my father for is – you never back away from anyone calling you an anti-Semitic name. Being called a kike or a dirty Jew was just something I couldn’t tolerate.

So you went to services.

I get on the bus. It’s a big gray school bus and there is a (bus driver) in there and I go to sit down toward the front of the bus. I was the only guy on the bus. And he said, “You f——— kike, you sit at the back of the bus.” He was pissed off because he had to take me on a Thursday evening and wait for me while I went to Jewish services.

What was it like afterwards?

I get an announcement (the next day) to go the administration building. I knew something awful was going to happen. I come in there and there is this lieutenant behind his desk. And he’s looking at me and he says, “Do you know what you are?” And I said, “I know exactly what I am. I am a recruit in the U.S. Coast Guard and I am a Jew and you are going to f—- me.” The guy says to me, “You are a filthy, dirty scrounge. Your fingerprints were found on your window cleaning detail.” I said, “I wasn’t even on a window cleaning detail.” He said, “You got 13 demerits in one day, that’s a record.” And then he called me all kinds of names. He didn’t say anything about being Jewish. They then took me out of my company. My head was shaved as clean as the back of your hand. I was put in X Company, which is a company when you are a total reject – some imbecile or violent or some crazy. They kept me out of my company for an entire week.

How was it after that?

There wasn’t a single day that went by where they didn’t do something to me. I was not allowed to eat with my company. I had no recreation. I was assigned to my bunk if there were days off. What happened was I had a Coast Guard manual and it was a big, thick book. I read that book over and over again. Every time there was a test, the maximum anybody could get was 300. The average score was 200. My scores were 293, 295. When we graduated boot camp, Roberts came up to me and he said, “You are going to make a fine sailor.” I just looked at him. I didn’t shake his hand. There was dead silence. Everybody knew what they did.

Then you were assigned to a ship.

They put me on a ship in Seattle with about 25 other men from my company – Echo 26. I get on the ship and this boatswain’s mate, he’s reading off the list of all the seamen. And he says, “Now which one of you motherf——— is Nadel?” And he says, “I am going to pack your sh——-,” whatever that means. From the moment I was on that ship, for three months, it was 18-hour days.

What did you do?

I ran the laundry. I complained to the commander. I said, “When I signed up for the Coast Guard, I was told I would move around the ship and learn different things.” And the guy said, “Oh, I see. You are going to run the laundry and then you are going to stand the midwatch.” So from 7 a.m. in the morning until 7 p.m. I ran the laundry by myself. I did the laundry for 175 men. Then at 12 o’clock at night, until 4 a.m. I was on the midwatch, which consists of steering the ship, being a messenger and then being on the flying bridge. They put me up there in a storm. I said, “This is dangerous, you are really going to make me stay out there?” So they gave me a rope to tie myself in, and I tied myself to this railing. We were taking green water, not the foam. If I hadn’t been roped in, I would have been washed overboard.

But you made it through.

I was on active duty for six months. I was graduated out of the Coast Guard and they call me in and some other officer says, “Nadel, I’ve looked at your records, and we have an offer for you. We would like to send you to Newport, R.I., to an officer candidate school. You have leadership skills.” I said, “Have you any idea what’s gone on with me over the last six months?” I said, “I just want out of here.”

Looking back, how do you feel about the experience now?

It was the best experience I ever had in my life. It made me grow up. Being in the Coast Guard was this coming-of-age experience – this life-changing thing. My life was threatened many times. I can’t begin to tell you the things. It changed me. I suddenly got very serious. School was effortless. School was fun. Nobody beat me up. The classes were fun. If not for the Coast Guard, maybe I would never have become an architect. The Coast Guard tested my mettle. Almost nothing I face scares me anymore. I just know it strengthened me.

How so?

Business is easy. Dealing with a client and saying, “You’ve got to pay, we can’t proceed with the work unless we are paid.” All these things toughen you up. I’ve had unpleasant experiences.

I know you lost your daughter Julie to cancer in 1992.

Everything pales in comparison. (In tears.) It is so sad. I know a lot of people who have lost their children. I was in a Young Presidents’ Organization group with 10 people and five of us lost kids. We all said the same thing: It’s just terrible. Business is easy. You know, when she was diagnosed, I knew right away she wouldn’t live. And I did everything I could. It was two and a half years. Terrible.

These difficult life experiences – have they shaped the causes and organizations you support?

I’m still not a terribly religious fellow, but I have an affinity to Israel. I am very involved in all kinds of charities, not necessarily Jewish ones. I am active in the Israel Cancer Research Fund. I am also active in the American Cancer Society.

So how did the Coast Guard lead to architecture?

When I got out of the Coast Guard a friend of mine told me about L.A. Trade Technical College. They had a drafting class. I got straight A’s. There was a professor there named Mr. Horie, from a firm called Cashion + Horie. And he said, “You know you can really draw. You are one of my best students. You’ve got to go to USC.” I didn’t have the money to go to USC (full time) but I went to night school for years and years until I was able to take my state board exams. In September of 1968 I became a licensed architect.

And five years later you started your own company.

I had a little house in Canoga Park and I had a little studio there and I was working out of my house. I knew a young fellow, whose name was Colin Gilbert. His father was Arthur Gilbert, a very wealthy, famous guy. Colin called me up and said, “I have an office building to do in Rosemead. It’s a 30,000-foot office building, do you want to do it?” I got that little job. It was 1973. It was wildly successful. Then I did another one on the other side of the freeway for him, a very cool building. They used it in a Jaguar commercial and all of a sudden I started getting a bunch of work. Suddenly I became the guy to go to, to build these office buildings.

How did you end up doing so much international work?

In the early 1990s, we were doing a lot of office buildings. I had an opportunity to go to China. Somebody said, “Come to China. We will pay for your trip. We want American designers here.” We got one project for a Pasadena company that makes TiVos. Their factory was in China – that was my first job there. We got all kinds of jobs in Asia. We have stuff in the Philippines and Vietnam. We have affiliate offices in Shanghai and Taiwan.

I understand you are transferring ownership in your company to some senior employees.

My plan is, roughly five years from now I will own less than 50 percent of the firm. In another few years I will be in my later 70s and the firm will be owned by others and I will have a founder’s agreement and that will let me work. It will give me some modest income and I can guide the company. Money doesn’t motivate me. Money is a side effect of something that you love to do.

What jazzes you these days?

The positive side of my life is I have two daughters and five amazing grandkids and I adore them – it’s like having your own children again. I travel for work a lot. Last year (Jeannine and I) traveled to South America. I will go to Asia and travel for work. I just was in Nigeria two weeks ago.

Did your parents appreciate your success?

Candidly, my father, Nathan, was a very unusual man. He was the antithesis of a Jewish immigrant: He didn’t work very much. I didn’t respect him. He said, “If you become an architect, I am going to have nothing to do with you.” Because every architect he worked for said, “I don’t like the color, paint that over again. This isn’t good enough.” He felt architects were arrogant and he didn’t really want anything to do with them. My mother, Mary, on the other hand, was a very nurturing woman. But when it came to school and me performing or me being inspired or pushed, they didn’t do a thing. The only thing my mother ever said to me was “Whatever you do in your life, don’t be like your father.”

Did you ever learn the root of your father’s issues?

I found this out after my father died. He was in care of a baby brother when he was 9 years old and that baby died. Either he choked in the high chair or fell out of the high chair. I think (his parents) punished him for that. He passed away when he was 68 years old, about 30 years ago.

When you examine your life, what do you draw from it all?

I look at my older brother who died at a young age. I had a young sister who died of a brain tumor. And me? Life I really believe, it’s a matter of luck. You get something in you that motivates you. So I think I’ve just been phenomenally lucky. Being in the Coast Guard was dumb luck; having asthma was dumb luck. It hasn’t been easy.

Herb Nadel

Title: Chief Executive

Company: Nadel Architects Inc.

Education: Failed out of Santa Monica City College; A.A, architecture studies, Los Angeles Trade Technical College; studied at USC School of Architecture.

Career Turning Points: Project architect and design team member for UCLA’s 5,000-seat Track and Field Stadium. Won significant design competition for the West Coast headquarters of Mercedes-Benz in Hollywood.

Most Influential People: “Daniel Dworsky, who felt enough confidence in me at only 26 years of age to place me in charge of the UCLA Track and Field Stadium, which ultimately unveiled my innate abilities as a serious architect, giving me the courage to pursue my career. My brother Richard, who inspired, provoked and ultimately challenged me to launch my own practice.”

Personal: Lives in Westwood with companion Jeannine Sefton; has two daughters: Jessica Nadel, 42, and Jennifer Nadel Zeitz, 41; five grandchildren.

Hobbies: Playing golf, skiing in the winter, traveling the globe for business and pleasure.