Occidental Petroleum Corp. is planning a major drilling operation in Carson, its first significant project in Los Angeles County in decades. And it may involve the controversial process of “fracking,” although the company said there’s only a small likelihood that will happen.

The Westwood-based oil giant has submitted plans to drill up to 200 new wells in an abandoned oil field just east of California State Dominguez Hills and not far from residential neighborhoods.

If allowed, the project could create hundreds of jobs and millions in tax revenues. But first, Occidental must overcome opposition from some of the same groups that sank previous attempts to drill in other areas of the county.

Environmental groups already are saying they object because new drilling may cause leakage through old wells, creating the possibility of blowouts. Beyond that, they claim, the land could sink and if fracking is used, groundwater pollution could result.

Occidental has scheduled a series of community meetings beginning later this month on the Carson project. A 10-minute video produced by supporters promotes the project as a means to provide energy while the nation transitions to renewable fuels.

The video, which will likely be shown at coming community meetings on the project, cites a study Occidental commissioned from the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corp. that claims the project will generate 300 full-time jobs and $70 million in annual economic activity – or more than $1 billion over the project’s lifetime. Carson and the county would get millions in tax revenue.

Once the project is fully running, Occidental hopes to extract up to 6,000 barrels of oil and 3 million cubic feet of natural gas a day for 15 years.

Focus at home

Saied Naaseh, associate planner in the city of Carson, said Occidental is expected to submit its environmental impact report this summer. The project is due before the city’s Planning Commission this fall, with the City Council taking it up possibly before year’s end.

The oil company must also obtain permits from several other state and local agencies, including the state’s Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources. If all goes well, drilling operations could begin about a year from now.

The project is part of Occidental’s recent strategy to concentrate on drilling and exploration activities closer to home, away from the risks of international turmoil – including “Arab spring” uprisings and moves by South American governments to nationalize their oil industries – that have rocked the global oil industry in recent years.

As a result, the company has recently focused on drilling in Texas and California, said Alex Morris, senior research associate with Raymond James & Associates in St. Petersburg, Fla.

Occidental, which is the largest natural gas producer and the second largest oil producer in the state – the largest is Chevron Corp. in San Ramon – had planned on natural gas drilling in its Elk Hills holdings west of Bakersfield. But, Morris said, the recent plunge in natural gas prices has changed that.

“Occidental is redeploying capital and rigs to more liquids-rich plays like Dominguez Hills,” he said.

The Dominguez Hills oil field is one of the oldest in the region, with the first wells drilled in 1923. In its document filed with Carson in March, Occidental notes that the field produced about 274 million barrels of oil before it was largely abandoned in the 1960s.

Estimates are that the Dominguez Hills oil field still contains an additional 400 million barrels, but much of that is in hard-to-reach rock layers. The filing stated that pumping and salt water injection are required to draw out the oil.

Occidental plans to use “directional drilling” to access many of these remaining oil deposits. In directional drilling, a single well bore goes straight down several thousand feet from the surface then bends sideways to reach the target deposit. This allows drilling from one surface site to reach oil deposits miles away.

Occidental has already drilled two test wells on the 6.5-acre site. The company said it will drill 130 production wells and 65 other wells for injections to free oil. All those wells will reach the surface of the 6½-acre site; one drilling rig will move along a track to maintain the wells.

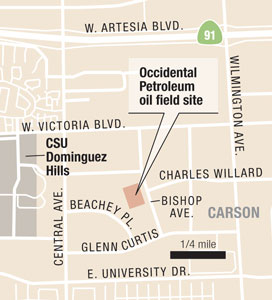

Much of the rest of the surface parcel near Bishop Avenue and Charles Willard Street will be devoted to separation and treatment facilities to prepare the oil and natural gas to move along pipelines to local refineries.

Environmental concerns

The parcel sits in the midst of an industrial tract bounded by Central Avenue on the west, Victoria Street on the north, Wilmington Avenue on the east and University Drive on the south. Two residential communities are near the site. Also, Cal State Dominguez Hills is west of the site, with about 11,000 undergraduate students enrolled. The Home Depot Center, where the Los Angeles Galaxy and Chivas USA soccer teams play, is on the western end of the university campus.

A spokeswoman for the university said the school has no immediate concerns about the project but is awaiting more information from one of the Occidental briefings slated to take place on the campus later this month.

But environmental groups – including the local chapters of the Sierra Club and the Natural Resources Defense Council – are already concerned.

That’s because the drilling could involve hydraulic fracturing or fracking, a process in which high-pressure injections of water, sand and trace chemicals fracture rock formations to dislodge oil.

A backlash against fracking has grown as critics contend it can pollute groundwater supplies. State and federal authorities are considering more regulation of the practice.

“We have included hydraulic fracturing as a potential element, but, based upon preliminary data, there is very little likelihood that hydraulic fracturing would be used in the project,” said Mark Kapelke, manager of engineering and operations for Oxy USA Inc., the Occidental subsidiary overseeing the project.

“If our plans were to change in that regard, we would be transparent, seek all necessary approvals, disclose our activities to the public, use best practices, operate safely and abide by all regulations,” he said.

Occidental maintains in the filing that if fracking is used, it would take place thousands of feet below the water table and therefore will pose little risk to groundwater.

That does little to placate environmentalists.

“The biggest concern we have is the potential for blowout,” said Tom Williams, a retired oil field specialist who now coordinates the fracking group of the Sierra Club’s regional chapter. “If the abandoned wells in that field have not been properly sealed, pressurized gas can migrate up through them and come up to the surface.”

Williams said there’s also concern that if fracking is done, some of the chemicals used in the process could leak through wells and pipes and into the local groundwater supply.

Occidental said in its filing it would use steel casings and cement slurry to seal off wells and prevent any groundwater contamination.

Williams said that another concern at all urban drilling sites is the prospect of land subsidence – or sinking – that can damage buildings. Residents in Baldwin Hills, where Houston-based Plains Exploration and Production Co., better known as PXP, has proposed expanding drilling operations, have alleged that subsidence has damaged their homes. PXP officials deny their operations are to blame.

To reduce this risk, oil producers typically reinject water into the formations from which they extract the oil or natural gas.

While all these environmental concerns appear formidable, oil industry analyst Morris said they are surmountable.

“Redeveloping an older field shouldn’t cause quite as much environmental anxiety as some other locations might,” he said.

Still, the environmental lobby is powerful in California. Twenty-five years ago, Occidental was forced to abandon plans to slant drill off the Pacific Palisades-Malibu coastline after environmentalists and local celebrities mounted a campaign to stop the project.